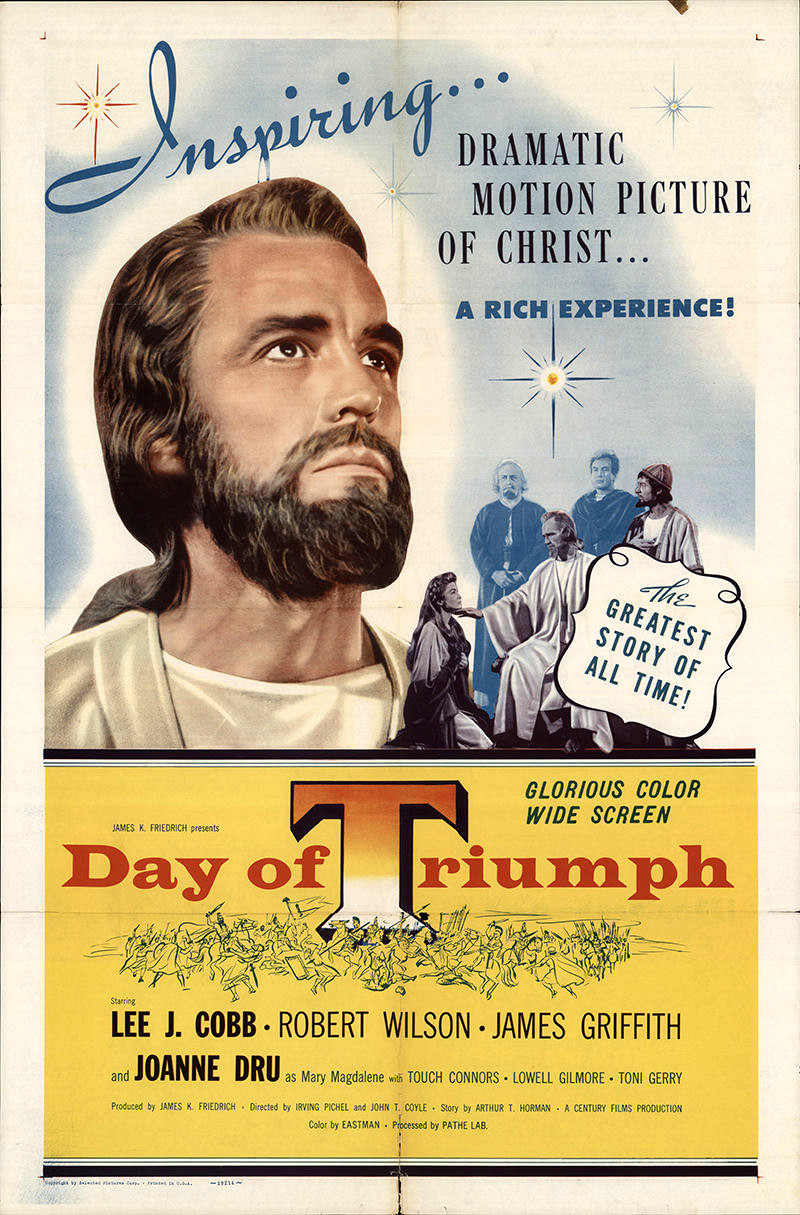

The first Color & Sound feature film about the Life of Jesus Christ

Watch "The Making of Day of Triumph" Featurette

Day of Triumph was produced by the Rev. James. K. Friedrich and released in 1954. His son, Rev. James L. Friedrich, wrote the narration in the above video and also wrote this article about the film:

“Day of Triumph”

By Rev. James L Friedrich

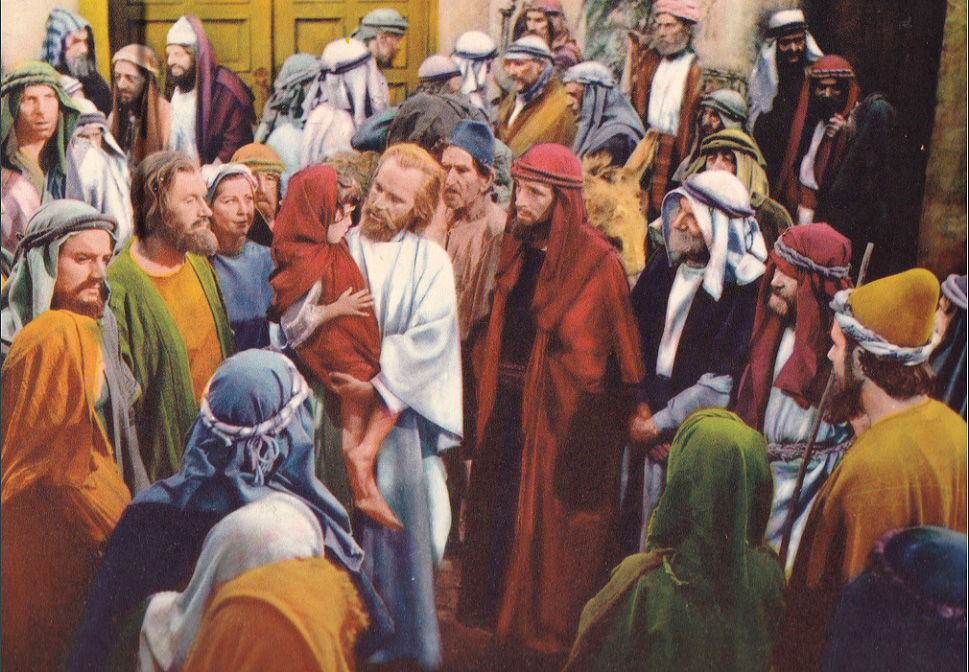

The very first shot of Day of Triumph establishes its uniqueness. Whereas most films of the period began with opening titles, the first thing we see in this film is Jesus, against a bright blue sky, speaking on camera for the first time in an English-language feature film.

“Listen!” he says. And before this commanding figure, larger-than-life on the big screen, towering above us in a low-angle shot, how could we not pay attention?

When movies were invented at the end of the 19th century, scenes from the Bible were among the most frequent early subjects, and dozens of short films about Jesus were made during the silent era. But commercial feature-length Jesus movies, presenting a consistent and persuasive sacred figure onscreen for two hours or more, have been relatively rare . Only two silent features–From the Manger to the Cross (1912) and The King of Kings (1927)–made Jesus their main character, and almost three decades would pass before the sound era saw its first English-language Jesus movie: Day of Triumph (1954).

Biblical spectaculars were popular in the 1950s. Ben Hur and The Ten Commandments were the decade’s top-grossing films. But Day of Triumph, a relatively low-budget independent production, was the only fifties movie to make Jesus the main character. The producer was an Episcopal priest, James K. Friedrich, the American pioneer of Christian filmmaking. After making his first feature film, The Great Commandment, in 1939, Friedrich produced dozens of biblical shorts for churches and schools before returning to the big screen with his most ambitious and moving work.

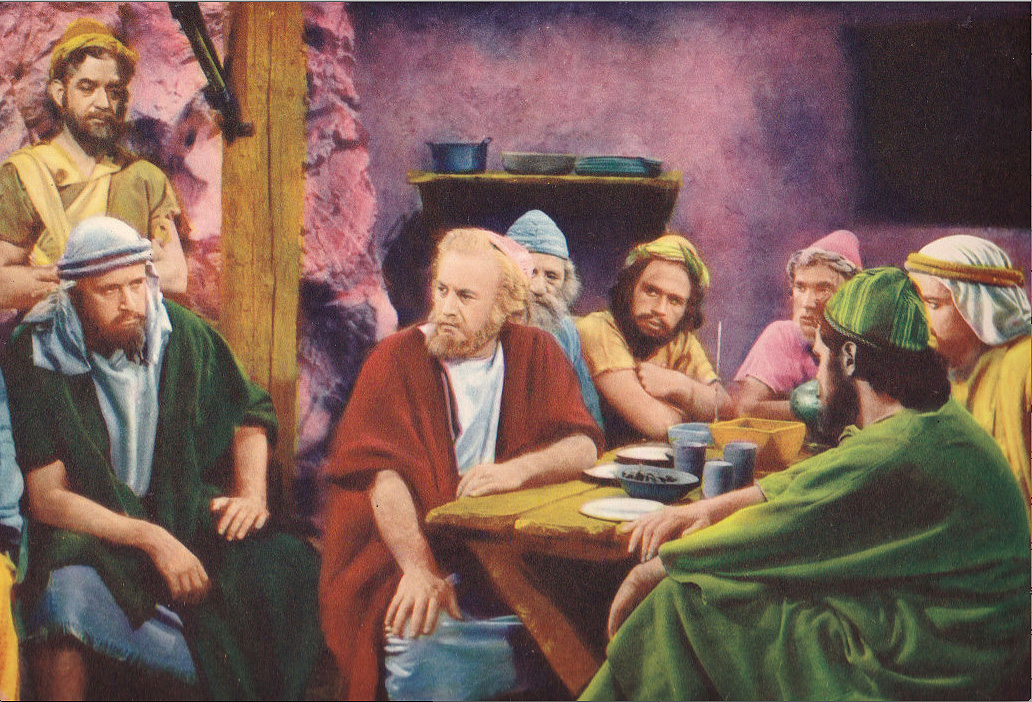

The director was Hollywood veteran Irving Pichel, who had also directed The Great Commandment. It would be his last film. Pichel died during post-production, and co-director Jack Coyle supervised the final release. The cast included some well-known actors. Lee J. Cobb, fresh from his celebrated performance in On the Waterfront, is a forceful presence as Zadok, fictional leader of the rebel Jewish Zealots. Romantic actress Joanne Dru, eager to escape her type-casting in Hollywood Westerns, plays Mary Magdalene. But the lead role went to an unknown, Robert Wilson, a minister’s son who had already played Jesus in Friedrich’s non-theatrical short films.

Playing Jesus is one of the hardest things an actor can do. The character is, by definition, some mixture of human and divine. But what does that look like or sound like on the screen? What sets Jesus apart from any other character? Is it his eyes, or his voice? Is it what he does or what he says? Is it the way people react to him? Is it the angle of the camera, or the music that underscores his presence?

Wilson bore a striking resemblance to popular images of Jesus. One critic saw both humanity and divinity in what he called an "uncanny blend of simplicity and sincerity.” Another noted that while Wilson doesn't make the Lord seem "pale or namby-pamby... neither does he make him the red-blooded he-man."

Striking the right balance between too cold (other-worldly) and too hot (earthy) is the role’s basic challenge. Later actors would try a more expressive personality for Jesus, with flashes of anger, moments of playfulness, or even some self-doubt. But Wilson plays Jesus with restraint, while avoiding the pious stiffness characteristic of earlier portrayals.

The scenes with Jesus stick close to the gospel accounts, without much fictional embellishment. The story of Judas, however, is largely a work of invention, imagining the betrayer of Jesus as a Zealot rebel committed to the overthrow of Roman occupation. He hopes to harness Jesus for political ends, but learns too late that Jesus cannot be manipulated or contained by human expectations. He is a mystery too large for the boxes we would put him in.

Day of Triumph opened in Hollywood in December, 1954. The Los Angeles Examiner praised its “unforgettable emotional…impact.” Newsweek said, “Compared with Hollywood biblical extravaganzas, Day of Triumph is a model of simplicity and good taste.” Life magazine gave it a splashy four-page spread.

But as is the case with most Jesus films, the treatment of Judaism in the gospel story came under scrutiny. Judas’ acceptance of blood money evoked a negative stereotype. And some found echoes of caricature in his dark features and pointed beard, making him appear more “foreign” than the other disciples. Ironically, Griffith’s Judas is one of the strongest and most sympathetic performances in the film.

Jewish sensitivity toward Jesus films is rooted in anti-Semitism’s long history of misusing portions of the Passion story to incite bigotry. While the makers of Day of Triumph themselves had no such intention, the detractors saw what they saw, and their complaints had a devastating effect on distribution.

The controversy made many theater owners reluctant to book the film, despite the enthusiasm of viewers and critics. Day of Triumph would only play in 20% of American cinemas before being pulled from general release. It would live on in television syndication, church screenings, and home video, but Friedrich never produced another feature film.

More than half a century later, Day of Triumph remains a masterpiece of Christian cinema, the first of its genre to use both sound and color. It is a product of its time in terms of cinematic look and acting styles, yet its unpretentious sincerity retains the freshness of good storytelling and persuasive performances. And its opening shot remains one of the great moments of the genre, as the Christ image, silent since the ancient beginnings of Christian art, is given a voice for the very first time.

(NOTE: DVD copies of Day of Triumph, including a behind-the-scenes intro written by Jim Friedrich, and bonus Cathedral Films’ Child of Bethlehem is available now at Christian Movie Classics and Amazon.com. The content is also available for download at Vision Video.